The MissTree of the Alchemical Woman (Part 2)

Tracing the roots of the symbolism of the Tree of Life, as a regenerative motif via the totemic form of the snake

This is a continuation of (Part 1 here) the Misstree of the Alchemical Woman.

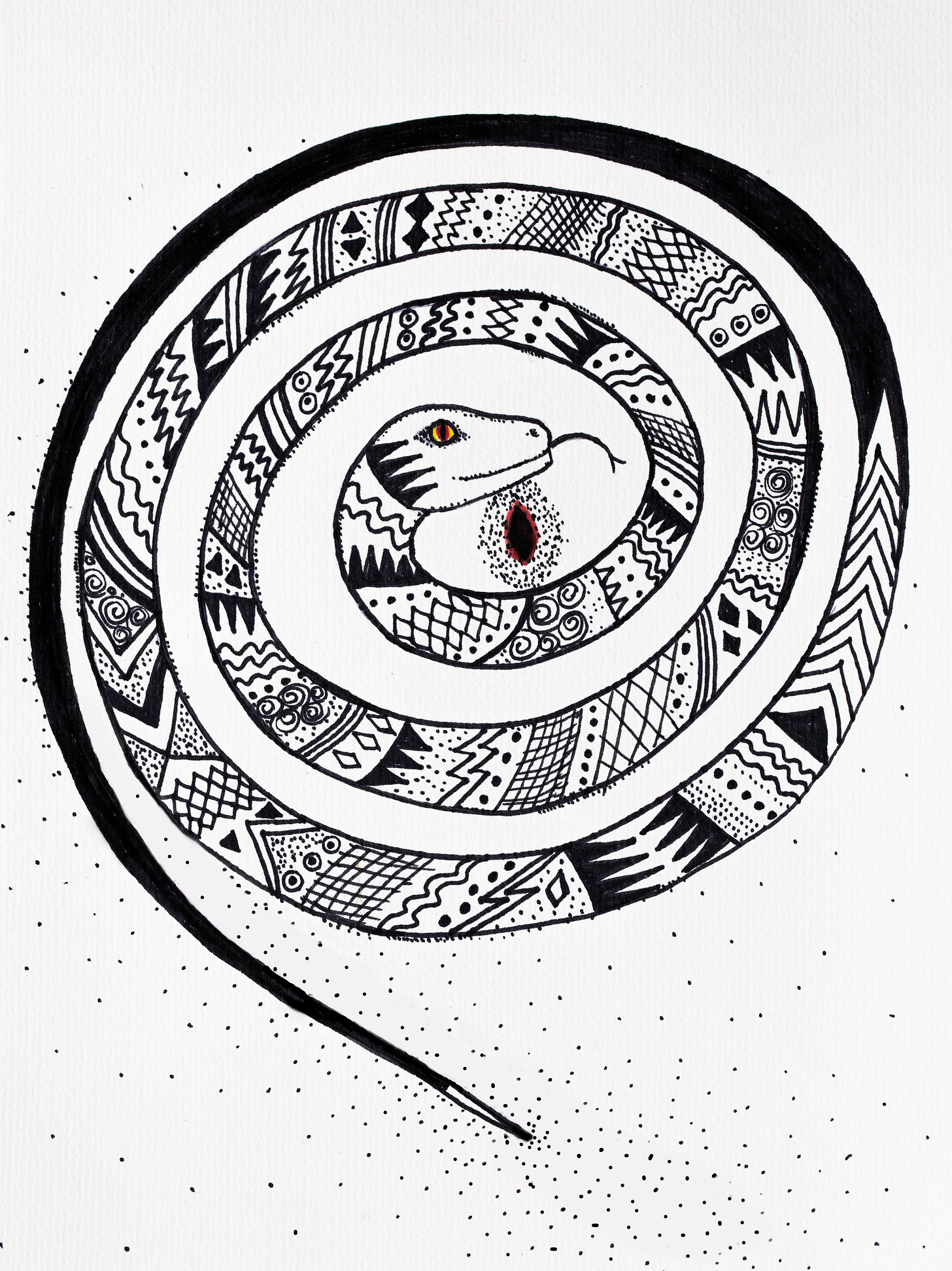

Above I sketched a spiral of a snake in the shape of a 9 (to play on the 9 period in Feng Shui and numerology of 2025), but also it's direction is anticlockwise or centripetal. In other words, spiraling inwards towards the centre which is congruent with the yin. The negative white space also forms a spiral in the opposite direction (clockwise), which moves away from the centre. Much like breathing encompasses both an inward and outward movement of air.

At the start of this month, we celebrated the Lunar New Year, which by now, most of us will be familiar with the concept of 2025, being the Year of the (Yin) Wood Snake in Chinese Astrology and Feng Shui (Chinese geomancy). So I thought I’d continue the dissertation in breaking down the symbolism of the “Tree of Life”, in its generative aspect via the snake, the second recurring icon found in its myths.

THE SNAKE - TOTEM OF FERTILITY AND BIRTH

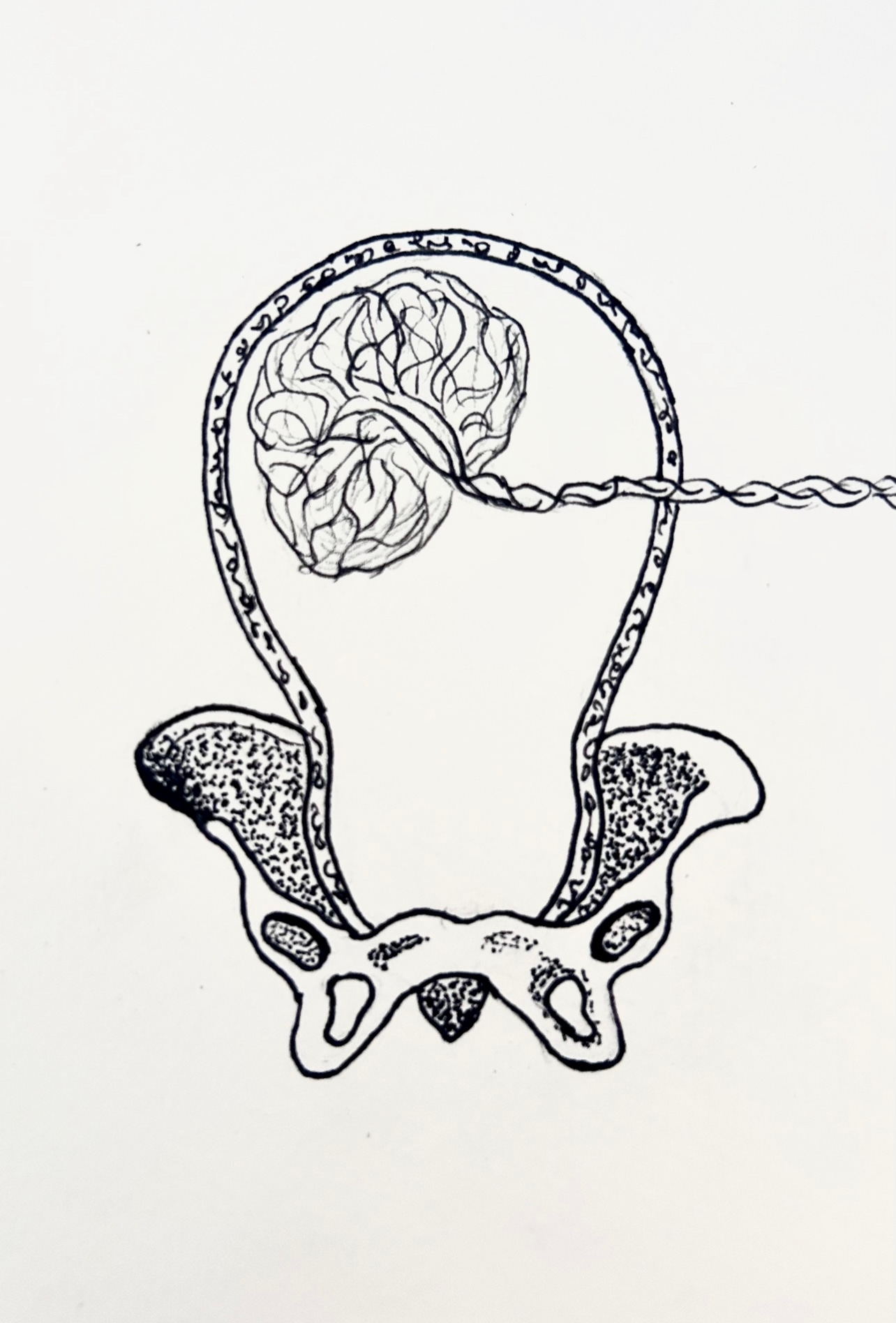

Above sketch by me of the placenta attached to the uterus and the umbilical cord which both feeds and evacuates waste to and from the fetus. The uterus sits upon the butterfly shape pelvic bone.

We find the notion of fertility and rebirth also prolifically represented by the snake/serpent/dragon, found across all cultures. The snake is yet another very ancient symbol of the Goddess religion, of feminine power, the Kundalini; by its embodiment of life force. We find its earliest depictions in cave art and stones engraved with zig zags and/ or coiled spirals which evolved over time into the more ornate, graphic designs found in shrines, temple walls, sculptures and art throughout millennia. Many argue that its form is androgynous, but more so, will perceive it as a priapic icon when fully extended and having an arrow shaped head. Curiously, nearly all venomous snakes are identified as having a triangular or arrow shaped head, as opposed to the more rounded head shape. Others posit the snake as the totemic form of the goddess, as they contend that there are probably more anatomical similes with the woman’s body. For instance, the yonic shape of its mouth when the jaws are wide open; and the way its body contracts and convulses as it swallows prey, have been compared to the contractions of a woman in childbirth. Of course, once the prey is swallowed, the snake’s swollen belly looks impregnated for a few days after, as it slowly digests.

Above is the Serpent-headed Madonna from Ur, suckling her infant. Iraq, dated to 4000BC. Notice the pubic triangle etched with numerous “v” shape engravings. (source Pinterest)

In Mesopotamia, we find the primordial creatorix Tiamat, who created the gods and is often described as a monstrous sea serpent or dragon known as “the glistening one”, as well as being described as a woman, although no artistic representations have been found from that period. A pre-Hellenic Mycenaenan idol discovered in the Acropolis of Sesklo, Northern Greece, dated to around 5000 BC, depicts a serpent-mother holding her serpent infant in her lap, while seated and covered in horizontal patterning of stripes, which archeologists deem indicative of snake patterning. We find similar iconography uncovered in Iraq - a serpent-headed Madonna from Ur, suckling her infant snake, dated to be around 4000 BC. Already, we can begin to see an ancient archetypal form linking the snake to motherhood, which maybe explains why the snake is often an emblem of fertility and protection in childbirth among many cultures. The Dogons of Africa tell a tale of a snake teaching women how to give birth, perhaps in symbolic reference to how wide their jaws can stretch open or their rhythmic belly contractions. Conceivably, this may explain why we have found many depictions of half snake women throughout mythology, which more often than not, are serpentine from the waist (womb) downwards, like the Der of Babylon, the Libyan Lamia, the Shahmaran of Turkish and Iranian folklore, Mami Wata of Central Africa, the Greek Echidna and the Naginis of India.

Popular depiction in Turkish art of the Shahmaran. Note as well the bird on a tree branch.

Above and below, the two sister deities or perhaps mother and daughter, from the Palace of Knossos, Crete, brandishing the sacred adders, dated to 16th Century B.C.E.

When I first saw these figurines from Knossos, I couldn’t help but imagine belly dancers, as they appeared to me to be dancing with snakes around them. I remember when I was learning belly dancing, there was an arm technique actually referred to as “snake arms”, whereby we had to create these undulating strokes. Overall, belly dancing feels to me as if mimicking the movements of a snake; with the hip shimmies, the figure 8 of the hips, the rippling contractions of the belly, even down to the undulating movement of the arms and hands.

The hieroglyph for the Uraeus meant both serpent and goddess. Once again reiterating that the serpent is one of the oldest metaphorical forms of the divine feminine. The Uraeus also later became one of the “secret names of god” listed in the Magic Papyri.

Maybe the serpentine umbilical cord is what ties the snake to birth and fertility. The umbilical cord is comprised of two veins braided around a central artery, which not only brings to mind the caduceus but also the hair braid. We find the braid or plait, often 3 sections of hair intertwined together among all indigenous cultures and often worn as a symbol of protection or a sign of puberty (when initiated as a menstruating woman). One of the symbols of the Hindu goddess Kali, is the serpent, as she is often flanked by them, as well as wears a crown of serpents. Her symbolic thread, known as Kali’s Snake, is said to represent the umbilical cord of creation, but broken it signified death. Much like the snakelike umbilical cord can sometimes strangle the fetus. Perhaps this severing of the cord may be coded into the myths of the slaying of the dragon or serpent. Also, the thread, which we will later discover in more detail, through the bird iconography (Part 3), links back to the Fates, who spin, weave and cut the Thread of Life. Neith (the Egyptian equivalent to Athena), one of the primeval Egyptian gods and in her oldest form she was represented as a golden cobra. Neith, like Athena, was the goddess of wisdom, war, creation, childbirth and weaving. Anyone familiar with Egyptology would recognise the rearing or upright cobra, the Uraeus symbol, found on the crowns of the Pharaohs, used both as a protective motif and as a sign of royalty. Later, we have the goddess Wadjet (Buto to the Greeks), who was known as the “Green One” was portrayed as a Uraeus (Egyptian Cobra) with large colourful wings and is perhaps the most notable snake goddess in the Egyptian pantheon. The hieroglyph for the Uraeus meant both serpent and goddess. Once again reiterating that the serpent is one of the oldest metaphorical forms of the divine feminine. The Uraeus also later became one of the “secret names of god” listed in the Magic Papyri. This dualistic nature of the snake as a symbol of birth and afterlife is also embodied in the sister-goddesses Isis and Nephthys. Similarly, the Akkadian goddess Ninhursag, known as “Mistress of the Serpents” was also “She who Gives Life to the Dead”. Again, this theory that motherhood, the vehicle of creation, is also intrinsically tied to the afterlife, the womb to tomb cycle.

An ouroboros found on a tombstone in the UK with notably 7 stars within. (source-Pinterest)

Birds and snakes share in the egg symbology, i.e. twice born; first as the egg and then the hatchling. Although 70% of snakes are egg laying, this was not it’s only characteristic to denote rebirth/ resurrection. In ancient times, it was once believed that snakes were immortal, as they shed their skin and appeared to be reborn anew, hence its association to death and resurrection. Likened to the belief that Wadjet’s eye had the power to heal and resurrect the dead while her wings were said to symbolise the breath of life. In my previous essay Blood Magic I tackled more deeply this symbolism between the snake and the woman. However, it would be negligent not to also mention it again here. Another aspect of the snake that is often compared to a woman’s anatomy, is in terms of her monthly shedding of the uterine lining, which is also a marker of fertility and has the potential to transform into the placenta, once impregnated. Accordingly, we also find in Hindu myths this connection between snakes and the menarche (the first menstruation), as it was thought to be initiated by copulation with a supernatural snake. Hence, the legend of the giant ruby jewel that sits at the centre of the cobra’s head (Nagamanikyam / Precious Stone), which the cobra was said to spit out on a Full Moon and New Moon, in prayer to the almighty, alluding to menstrual rites that coincide with the moon cycle.

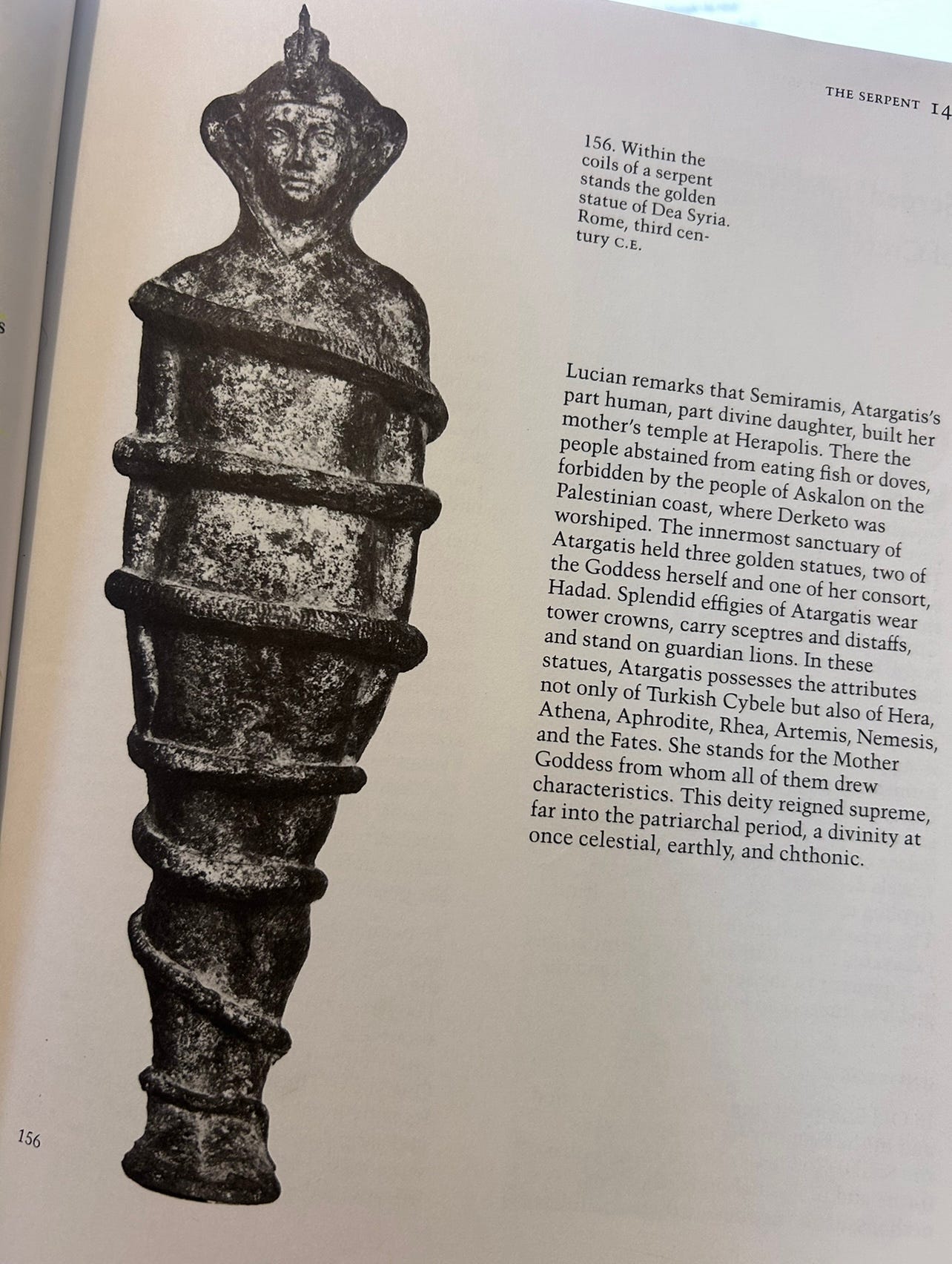

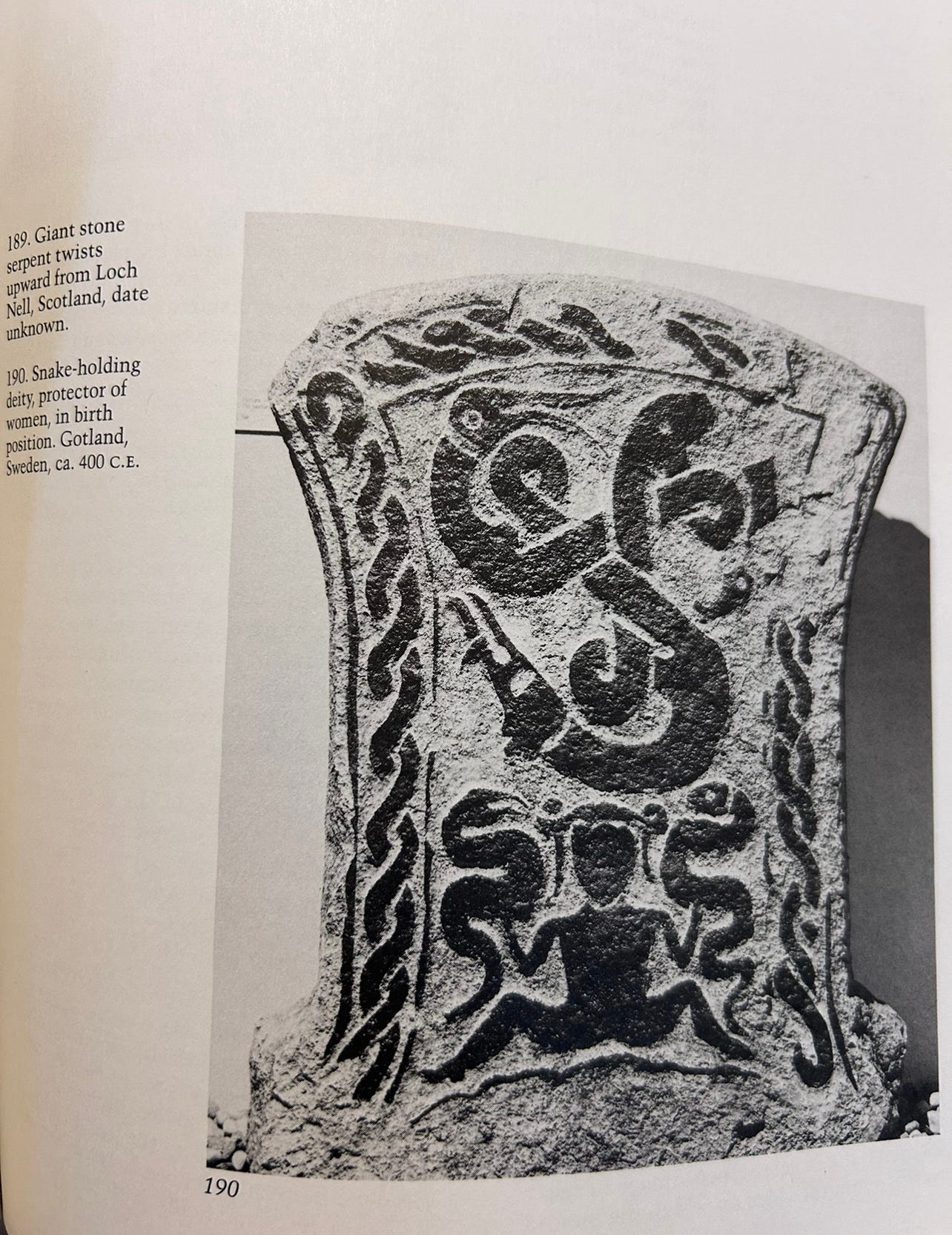

Snakes are indicative of life force, as reinforced by concepts like the serpent goddess Kundalini, that lies coiled at the pelvis (where the woman’s reproductive organs also lie) and is symbolic of the inner power and wisdom of the human body, as it rises up like the upright Uraeus, through the seven wheels of energy or chakras. This notion is reminiscent in the statue of Dea Syria, where a large serpent, is wrapped around her body seven times, yet looking peaceful and as if being mummified. Interestingly, the German word for spinal column, wirbelsäule, actually translates literally to whirl/ vortex column. Once again, we see a connection to the ancient symbols of the spiral, coiled snakes, swastikas, whorls and spindles which have all been identified as totems of the divine womb, the vortex of creative life force contained within it.

Above are photos of pages opened up from book “Lady of the Beasts” by Buffie Johnson

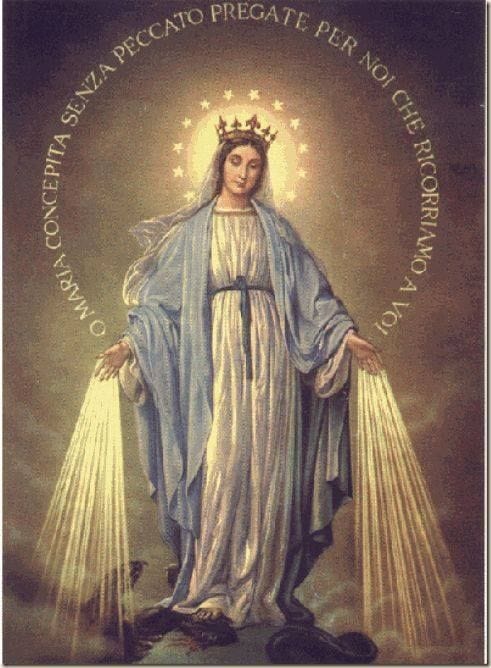

We are probably all familiar with the medieval artistic depictions of the Virgin Mary, often with a sash or belt which is said to indicate “pregnancy”. Notice too how one foot crushes the serpent coiled at her feet.

A Statue of the Aztec Goddess, COATLICUE ( Mother of the deities/ Skirt of Snakes)

Perhaps the least spoken about, yet a recognisable and repeated motif in images of the goddess, is the snake girdle. Snakes intertwining around the hips and waist of the Cretan goddess, Kali’s snake girdle, the Medusa at Corfu also wears a girdle of copulating vipers and the Aztec goddess Coyolxauhqui (daughter of the Earth Mother, Coatlicue, pictured above), also wears a belt of snakes. What is the meaning behind the snake belt? According to the Lady of the Beasts “The belief among Jews that the binding of the belly with snakeskin assured easy delivery and that a snakeskin girdle worn during delivery was a protection against mishaps”. It now becomes painfully obvious that the snake girdle or belt depicted across civilisations was an ancestral aid and comfort to women in childbirth. This now sheds new meaning on the biblical god’s punishment to Eve, to experience “pain in childbirth”, because she disobeyed and listened to the banished Serpent, henceforth, separating Eve from her instincts and primordial traditions. Could this allegorical tale be indicating to us an actual demarcation in time when women loss their bodily autonomy as it pertained to childbirth and midwifery customs? A history we saw repeat numerous times, as recent as the 20th Century, with the increase in hospital births, when it became the norm to lie unnaturally on one’s back. Therefore, could we equate the steady decline in snake symbolism, as it lost favour as being a protective aid in childbirth, to the demonisation by the biblical god? Could this also explain the higher percentages of women vs men who fear snakes? Fear is often a learned behaviour. Even this video shows an experiment with babies who show no signs of fear when introduced to snakes. It would appear from this video alone, that our fear of snakes is something we learn, dependent on our cultural and societal education. In patriarchal Christianity, we often find imagery of the Virgin Mary, standing upon the snake, her foot crushing it’s head. Obviously, they are referring to the serpent of Eden, an evil symbol to be destroyed, but part of me also wonders if it is symbolic of the suppression of the wild, instinctual feminine.

“The belief among Jews that the binding of the belly with snakeskin assured easy delivery and that a snakeskin girdle worn during delivery was a protection against mishaps” Buffie Johnson, Lady of the Beasts

Perhaps this is an opportune time to share a personal experience with you, that many years ago, changed my whole perception about snakes. A bit of backstory first. I was raised Roman Catholic and essentially indoctrinated to fear snakes as evil entities. In fact, my Grandmother used to advise me, that if I dreamed of a snake, that the snake represented an enemy I may have in real life, and that if given the chance, I must kill it in my dream, symbolic of my overcoming that enemy in wakeful life. Now, as a lucid dreamer from a very young age, I actually dreamed of snakes quite frequently and would always ensure I’d slay them before awakening from the dream. I feared snakes so much so, that in real life, my go-to instinct if I saw one, was to kill it. The only time I actually killed a snake, was when I was a teenager and was gardening with a cutlass (machete) and upon entering the garden shed, the skinniest little snake (perhaps the harmless whip or vine snake) bolted across my path and I instantly chopped it with the cutlass. I actually felt very upset afterwards that I killed it, when I discovered it was a harmless little snake. It was not until I migrated to Australia from the Caribbean about 20 years ago, that I had another face to face encounter with a similar garden snake. One day, to my surprise, my husky was barking furiously outside the front door. I naturally went to see what was wrong with him and to my surprise, saw a beautiful, bright green vine snake bashing itself against the screen door, trying to escape from my dog. At first, seeing the outline of a snake through the screen door, I worried that it was one of the many venomous snakes we have in Australia and I just wanted to get my dog away from it. My dog refused to come to my calls to the backdoor. Then, upon examining it through the door, I realised it was a harmless snake and my aim now changed, in that I saw my dog as the threat to this skinny little green snake. So I went outside and grabbed my dog by the collar, allowing the snake to escape into some bushes. That encounter stayed with me ever since and I remember the days and weeks after it, I was obsessively researching snakes and their symbolism, and what such encounter could have meant for me personally. Long story short, one day it hit me like a ton of bricks, actually bringing me to tears. The snake, who I was afraid of all my life and taught to destroy upon seeing, was in fact, representative of me. The little green snake that was thrashing itself on my front screen door, was that literal knocking at my door. It awakened within me, the creative feminine force that I was denying myself in so many ways, because I had been taught to fear it. Essentially, I was more afraid of myself and the power that lies dormant within all of us.

The serpent under the foot of the Virgin Mary, here depicted with an apple in its jaws.

Hopefully, I have brought forth a glimpse into how intertwined snake symbolism is with the divine feminine principles. In this essay, I’ve only explored the snake within the theme of procreation in terms of the tree of life symbolism. The next theme I’ll address later, is its pythonic aspect, returning full circle to the snake.

Thanks again for your time in reading and please feel free to share in the comments, other examples you’ve come across that can either add or challenge to what I’ve outlined herein. My Substack is a personal diary so to speak, of my research and my digestion of same, as I do not claim to have all the answers, definitively.

Stay tuned for Part 3, where I’ll address the bird symbolism as it relates to the Tree of Life iconography.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SOURCES

Lady of the Beasts (Ancient Images of the Goddess and Her sacred animals) by Buffie Johnson

The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets by Barbara G Walker

The Woman’s Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects by Barbara G Walker

The Language of the Goddess (1989) by Marija Gimbutas